My Cheesemaking Travels, Ireland, 2016

I have taken my annual leave to work in a factory. For the first few hours I keep hoping it isn’t true. I wait for someone to shout ‘just kidding!’ but no one does. Surely the cheese of my hopes and dreams couldn’t really be such a terrible let down? Such a betrayal of the story I told countless customers when I was a cheesemonger? There’s a moment of dread, a sense of mounting fear and frustration and then I remember that I’ve been here before. I’ve already learned this lesson; you don’t get to choose what you learn. Expectations will put a ceiling on what I can get from this experience. Open the mind.

Once I’ve started trying to reorganise my vision of what the next few weeks will be I mourn quietly for the closed herd I’d dreamt of. I was once told (by a cheesemonger who should know) that this carefully raised herd had been in the family for generations, that they bred all their replacements – careful never to buy in – and that the milk of this lovingly cared for collection of cows was the real secret behind the wonderful and unique flavour. Today Paul (the husband of Claire who created the cheese) told me with feeling that he “didn’t give a tuppence about cows”. The Irish government paid for cattle and was committed to supporting the dairy industry so he bought 60 animals in the mid 1970s when he came back to the farm. No love. No careful rearing and breeding. No passion. Just a need to survive and make the land pay its way.

The next generation, who are now running the business, are a revelation of their own. Lisa is Paul and Claire’s only daughter and a force of nature. Other people seem to be a mystery to her. There’s a chasm to bridge and she launches herself across the void with an enthusiasm that’s hard to get used to. You know she’s doing her best but remain unsure as to why she thinks you and everyone else are so hard to reach. These attempts to influence are exhausting and the end result feels a little sad. I wonder what it’s like to feel so isolated. My experience of the ‘Lisa Phenomenon’ came to a head last Friday when she quite literally circled me while discussing my hours for the following week. I was forced to turn on the spot, first in one direction and then the other in order to remain facing her while she spoke. This continued for several minutes until I got dizzy and began to lose patience. It appeared the only option was to stay still and allow her to come round again rather than continue to chase this rather ridiculous tail. Hilariously this seemed to throw her and the conversation ended rather abruptly with me facing a blank wall and her talking to the back of my head.

The voice of Claire, the creator of the cheese, is absent here. She is never spoken of; a weird vacuum I could feel even in my first week. Lisa and her husband Martin were generous with their time – Paul too – and there have been lots of conversations but no Claire. It seemed so strange because her name sits prominently on every single product line. She famously came up with the cheese in the first place – why would her husband and child say nothing about her? It’s like the whole family sits round the table when it comes to running this business but the creator’s seat is empty.

Back to the factory. They managed to get a 6.5 million euro production plant built with the support of EU funding about 8 years ago. It means they have masses of capacity to expand, they’re probably at about 50% at the moment and at the rate they’re going I’d say they have a pretty decent chance of needing it sometime soon. There’s a waste treatment plant, the farm and the land and ‘the factory’. I say ‘factory’ because Lisa has banned anyone from calling it that. A fascinating narrative of denial that means I was oblivious to the fact that I was coming to work in the aforesaid ‘factory’ but never mind.

They produce around 320 tonnes of their main cows milk cheese and about 30 tonnes of a sheep’s milk cheese a year. That’s a hell of a lot of cheese especially when you consider that an individual cheese weighs about 1.5kg. My maths has never been a strong point but that looks to me to be about 233,000 cheeses a year. This level of production from a ‘farmhouse’ operation is impressive, however I’m afraid I’m using the inverted commas again. Technically the definition of a farmhouse cheese is that the milk should only come from one farm and be made on that farm. The business is now buying in more milk than it produces, milk which is from a co-operative so therefore covering a pool which will include milk from several other farms. They say these farms are all within a 25 mile radius – in Ireland this isn’t too great a challenge it being the land of great grass and dairy – which in fairness does at least gives some indication of a commitment to local supply. They could (and I think do) also argue that they are farmhouse because the cheese is technically made on the farm but I’d say it’s stretching it a bit.

Anyway, it is what it is and I just have to accept that. The most interesting message and outcome of all this is, in honesty, that I would never have chosen to come somewhere like this so it is probably invaluable and where some of the lessons that I most need to learn lie. The farmhouse cheese movement in Ireland is serious business and so far it seems most are in it for exactly that. I have to admit to not having come across any of the ‘worthy’ passionate cheesy people I’ve been looking for in my three years of these adventures. Maybe I have to accept that everyone is making a calculated move when they select which bit of their story to tell and sell and that the die-hards can’t be heard because they simply don’t exist or are too small to make an impact.

Into the factory we go. The best way of describing it would be to send you the floorplan. It is coded and defined in dots and lines showing who can go where and at what time. The area has zones of red, white and blue (surprising in Ireland) and white jackets with collars that correspond to these colours. Appropriate clothing must be worn at all times in addition to the correctly coloured hairnet and footwear. I will save you the task of trying to understand and fake interest in all this (I made a transparently half-hearted attempt at my induction) and simply say there is a packing section plus fridges (by which I mean several huge rooms) which I am not a fan of and a production section where the cheese is made which feels a little more akin to the homeland of ‘real’ cheesemaking that I yearn for.

We will say no more about packing other than that it is dire. Everyone seems to hate working there and I finished my first shift, which consisted of making hundreds of cardboard boxes, blue plastered up to my eyeballs as finger after finger started bleeding from the constant bashing and crashing as I clumsily attempted tasks everyone else seemed able to accomplish with ease. Make a box, put a cheese in a box, put box on pallet and so on. Packing is where you go to lose the will to live. I feel for the women who work there. They apparently used to chatter like birds but under the current dictator’s tyranny (a man called Malcolm who quite clearly has a serious insecurity complex) are silent and mutinous. I give and get minimal chat in packing. It’s a relief somehow but means I learn almost nothing when I’m there other than the realities of working on a production line; something I’m not entirely sure I either wanted or needed to learn.

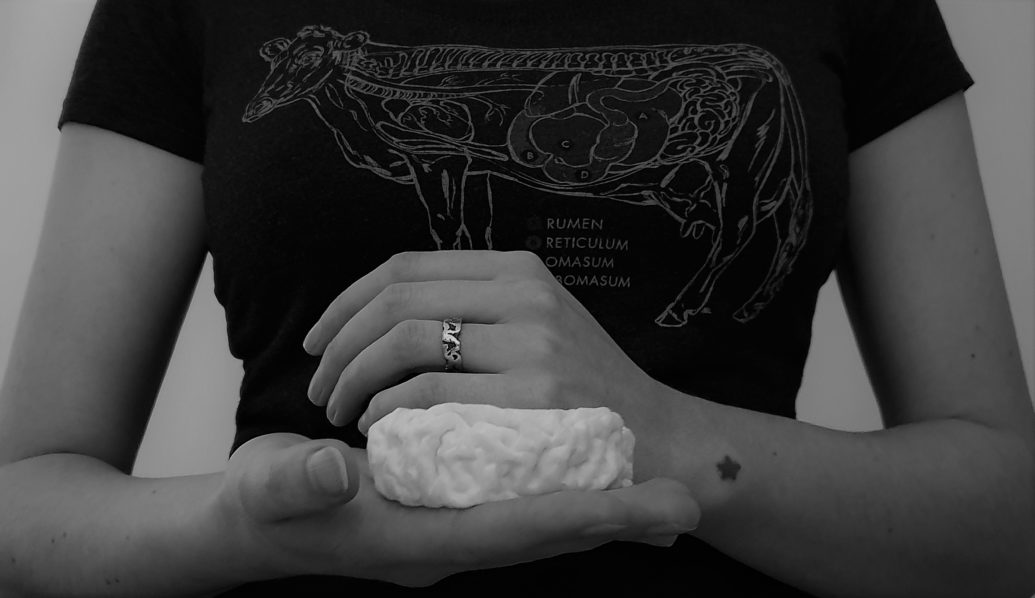

Production is interesting. Computer controlled cheesemaking but nonetheless interesting. I’ve never seen cheese made like this before, it’s eye opening and I’m sure it’s a good thing for me to learn about and be aware of albeit reluctantly. Their point of difference or USP as they would probably like to call it is that they still cut their curds by hand in open topped vats. There are eight of these that sit on a raised platform like large baths in a sauna. They are half cylindrical in shape and bowed like a cow’s stomach; hung low, perfectly rounded and full. These eight vats feed into a huge and, to my mind, monstrous looking moulding machine. I am genuinely crestfallen that no moulding takes place by hand here. They show their shiny machine to me with pride and all I can do is watch dried up raisin like curds being hurried along a rotation platform before falling to their doom below, topped and tailed by knives as they go. This all takes place behind metal bars, for health and safety reasons of course. It’s honestly slightly heart breaking to watch this wonderful cheese being made in a gigantic metal cage. All I want to do is tenderly touch the silky slippery soft curds of my cheese making dreams but in this creamery there are rules that will be enforced; you can look but no touching allowed.

However, there is cheese being made and aged and I can smell the smells I’ve missed and discover new tricks I’ve yet to learn. The people are interesting too with more chat than ‘Women’ as my Czech housemate calls the packing team. Clem is their longstanding Dutch head cheesemaker. Uncommunicative and constantly reeking of nicotine I think he may actually be a kindred cheese spirit if only I could get him to talk a little. Daniel is their more recent cheesemaking addition and has fascinating Polish observation of ‘The Irish’. Apparently they are backward because their windows only open one way and they have two taps rather than one. He is amiable and helpfully answers an unending stream of questions from me at 5am though so I am grateful to him. Dave is a genuinely lovely man though clearly un-enamoured by cheesemaking, he readily and regularly expresses incredulity at ‘all this fuss about cheese’. I don’t know what to say except admit to being one of those people who really is rather fussed about the whole thing. Billy is the other member of the team who I feel I must mention as despite some of the negatives of this cheese adventure it really is shifting things for me. I don’t know if it is seeing so much of what I know I would not want to do but this is the first time I have seriously started thinking about what I’d specifically like to try making, what books and equipment I will need to buy and how to create a ‘cave’ aka fridge at home for aging. I think the significant step has been tentatively sharing my pipe dream with some of the people I’m working with. Billy played a significant role here as he responded to my story by repeatedly stating ‘you’ve the right idea so you have’ constantly throughout an entire day of working with him. Granted this got a little wearing but when he brought in cheesemaking notes from a course he had attended the next morning I could feel the yearning of a man who never quite got round to pursuing his own dreams so desperately wants to make sure someone else will.

As I walk along the turning corridor, spike cheeses in the soft sucking sighs of the brining room and turn cheeses in a chilly humid haze I know there is still something meaningful happening here. Not played out quite in accordance with my purist principles of course but then who can keep up with those? This family business has been going for 30 odd years, is a huge Irish success story loved by local people employing nearly 20 people full time and exported throughout the world. It’s no mean feat by anyone’s standards and an achievement to be admired rather than judged.

So, here I am. Struggling a little but still glad to be where I’m at with time to clear my head, learn and ponder my options. The lilt of Irish voices and endless greens of the countryside ease my frustrations as does the joy of milking again. Who knew a person could be so thrilled to have their hands and arms covered in cow shit. Though I must admit the best milking so far was a sunny afternoon when they had been grazing and lying in wet grass all day leaving them with the cleanest udders I’ve ever seen. It’s difficult to describe the precious and reassuring nature of that lovely, soft, gentle warmth. Something many wouldn’t risk being in the inevitable firing line for but it makes my day.

On which note, love from the cows and the cheese and from me.

Emma

*names have been changed